Joseph Scrivner: When someone asked me if I would do this, I said, “Could be, could be not.”

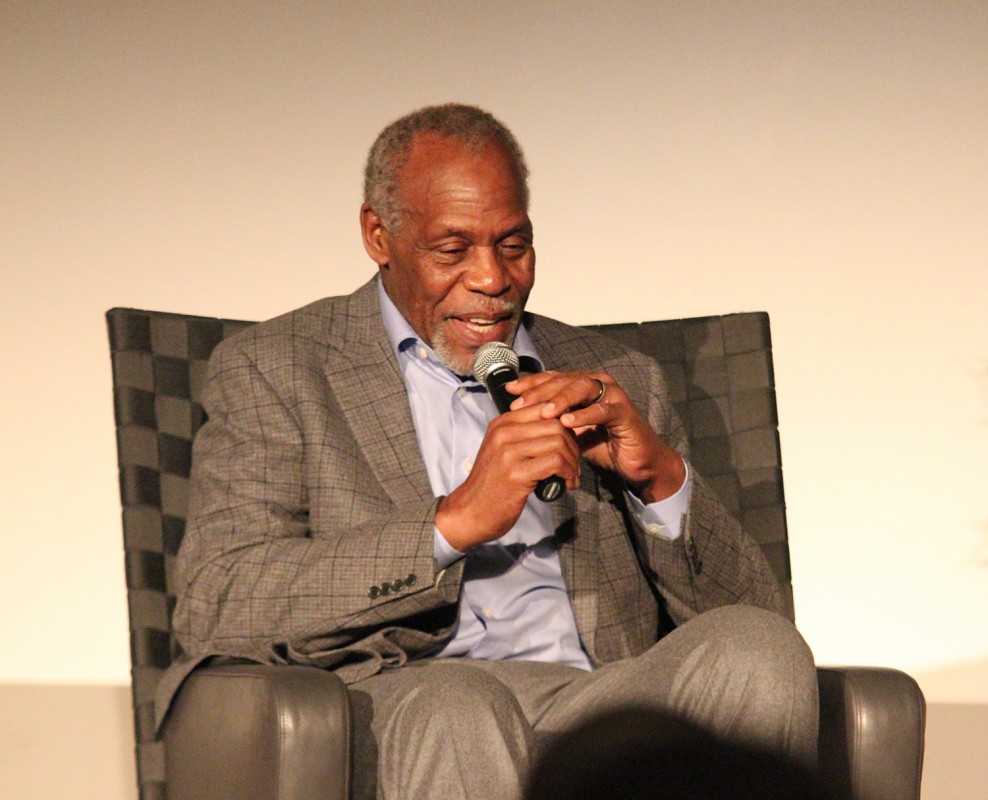

Danny Glover [laughing]: Could be not. As I watched this reel, I thought about my mother, which I often do, my mom and my dad. First let me apologize. I could have worn a suit and tie. But tennis shoes, athletic shoes, felt a little bit more comfortable. I’m not promoting New Balance even though most New Balance shoes are made here in the United States, not overseas. But I remember early in my career, I’d left my job and I worked in community development in city government for six and a half years from June of 1971 till the end of 1977, when I decided that my life was changing and I wanted to try to do something different. I was passionate about the work I did as a community developer with the Model Cities Program and the Office of Community Development, especially with men and women in particular communities, communities that had been disenfranchised, communities that didn’t have a long and stable political history. The way in which they took the moments and began to demonstrate in real life the kind of objectives, the kind of needs and anticipations and possibilities of what could happen in their communities. It was an extraordinary moment in what I call grassroots organic democracy.

And all this emerged simply out of the movements that began long before the civil rights movement, but certainly were nurtured and found their way and development from the movement itself and subsequent movements that came after that. I left the job and I go by my mother’s job. She was a supervisor at the U.S Post Office in San Francisco on Seventh and Mission. I would go by there just to see her extraordinary smile. If you want to understand me, you have to really understand how much my parents meant to me, and meant to all five of us siblings. The first time she saw me was in a community production of “Mice and Men,” and I played a big character, Lenny, in that play. James Earl Jones had played Lenny in New York some time before. So my mother came backstage after the performance. She was looking around surreptitiously and she said: “Son, the people said you can act” (laughing)! So, she had made a survey and listened to what people would say. That’s how precious my mom was. Whenever I would go and see her, and this was like 1979, 1980, I was starving like Marvin. I come up just to see her smile, and she said: “Come on, Danny, I want you to come and meet some of my employees.”

So what happened was she would begin the conversation, “My son Danny, he’s an actor.” And it was if she had a new word in her vocabulary: ACTOR. And then she would say: “Oh, he’s an actor” and just before they could say, “What has he done?” she would say, “Oh, he hasn’t done anything yet, but one day he’s going to do something important.” Only my mother.

I just want to thank Ed (Mullins) for the introduction. When I looked at this, and you look at it from a vantage point Ed mentioned, “Places in the Heart,” and my work in “Places in the Heart” is dedicated to my mother. Unfortunately, the same day I was told I would do the role, my mother died in an automobile accident, that same day. So I got that extraordinary news, and then I had to go and identify her body because my dad was so devastated. So I had to get on a plane, go to Grant, New Mexico, to identify the body and everything else. It’s so typical, because I had three nephews in the back seats, and one brother in the front. No one else got a scratch. Iwas like my mom said: “Lord, if I had to leave, don’t hurt my babies.” That was her. She was the epitome of all that. In that sense, I think a great deal of what I’m about is about my parents. I talked about it, I talked around the table, so much was about my parents, who they were, how I watched them as parents, young adults. And certainly, the things they identified that were important in life were also those things I found myself attached to.

As a child, I remember watching the Montgomery Bus Boycott on television. Television was a new phenomenon. I’m 71 years old, and it was a new phenomenon. In some ways, I was gauging not only my own response to that, but I had the validation of my parents and the way in which they celebrated and embraced the moment as well. They worked at the U.S Post Office in 1948, and they were very much involved, in not only the local but national alliance of postal employees. The demographics had changed in most places, probably here as well, where African-Americans were hired to come to the post office. My dad had been a veteran in the army during World War II and there were certain special considerations for that as well. But all those things kind of defined my early life. And then, a movement happened that found itself engaging not only to veterans.

We talk about Dr. King here today, but Dr. King would talk about the enormous mobilization that occurred around these movements. We must look at the civil rights movements as a continuum of the struggle for justice. From the time the first slaves arrived here, whether through the abolitionist movement [and] the struggle after the emancipation proclamation and the civil war and reconstruction. I think one of the extraordinary books to read is the W.E.B, Du Bois’ “Black Reconstruction in America.” It’s an enormous study where it refutes all the various lies they were told about African-Americans’ contribution to reconstruction, the introduction of public education, not only for black children, but all children, for poor white children as well.

So, the civil rights struggle was about Ida B. Wells, the great writer and great journalist who organized an anti-lynching campaign in 1896, the year of Plessy vs. Ferguson. I think of Dr. King as a continuum of that struggle. I was talking to students about when I went to Howard Law School some years ago. They have two floors dedicated for all those classes that graduated from 1896 to 1954.

Plessy vs. Ferguson, Brown vs. Board of Education — so all those kind of things when I felt in my mom, my mom who would always tell us children, part of my moral underpinning, what she said “I’m eternally grateful for my mother and father.” Her mother and father — my grandfather was born in 1892, my grandmother in 1895. They both saw “The Color Purple” and they lived to be 99 years old (applause). And when she said, “I’m eternally grateful for my mother and father. I didn’t pick cotton in September. I went to school in September.” She was grateful because my grandparents made enormous sacrifices to send all three of their children to school in September. Consequently, my mother graduated from Paine College in Augusta, Georgia in 1942. Ironically and so prophetically, her grandmother and my great-grandmother Mary Brown, the family matriarch. She was born in 1853, freed by the emancipation proclamation.

So it is a journey, and I think what has helped me throughout my life and throughout my career is that I’m a part of the journey much larger than me, much bigger than me, and much bigger than just African-Americans, not simply just African-American. When King talked about his work, he said, “I’m not simply in the business of — and I’m paraphrasing — integrating African-Americans. I’m trying to save this country’s soul.” He made that very clear. So when we talk about his legacy, we talked about Dr. King’s legacy, and realizing the dream, is that how do we save this country’s soul (applause).

Every time that I think about the profound wisdom and love, love, when Dr. King talked about the beloved community, with his speeches. I told the students in his speech “Beyond Vietnam.” He uses this from John 4:12, “Nobody’s ever seen God, but if we love each other, God lives in us.”

We got to love. Love is transformative. It’s not how many toys we get, how many trinkets, how much technology, it’s love. And hopefully in future generations that becomes the profound way in which we express real change (applause).

Joseph Scrivner: I tried to resist “The Color Purple” references as I thought about tonight. But I remember when “The Color Purple” came out, and I remember some of the backlash, about the presentation of African-American men. Given the issues that Alice Walker dealt with in her novel that are presented in the film, “The Color Purple,” and given more recent events about sexual harassment, the #metoo movement, how do you think those things vindicate what “The Color Purple” tried to deal with, first as a novel and then a movie, which you bravely and courageously play a difficult character to portray and present?

Danny Glover: I think, I don’t think that Alice Walker or the film or the book needed any vindication at all. And I would have been really dismayed if there had not been such a vibrant, discourse in communities, in cities. I was in Chicago during the play, right through the midst of that, and everywhere there was a conversation about “The Color of Purple.” I would have been dismayed if there hadn’t been that kind of conversation. Because we have to also deal with the way in which African-Americans are portrayed, from the very beginning, from before films, and everything else through the kind of stereotypical images that we saw around that they represented. But we also deal with that we are human beings too, you know, we are subject to the violence, all the other things. That doesn’t make it become the identity of an entire race. But like anybody else, we are human beings, in a process where every single one of us needs some ways in which we heal with each other. Men, whether they are white, black, Asian, whatever their color, brown, men have issues with women. That’s been historic in some sense, that has been a historical phenomenon. On the one hand, if we evolve and clearly create the path toward building some sort of transformative community, world, country, we are going to have to come to terms with that, absolutely without a doubt.

So in the sense that I felt the conversation was healthy and it was needed and from both vantage points, how the industry itself, the industry which creates identities, the industry which in some sense of uses and perpetuates certain identities at the expense of others as well. And I think at that point in time we needed that kind of discussion about that. Did it exactly change the issue? No. We talked about the violence against black women. The violence against black women goes back to slavery, absolutely. Do we have to do that? What did (James) Baldwin say? “We are not able to live with our truths.” If we cannot live with our truth and our true path, we are trapped in it. So in some sense, in every facet of our history, in our lives, me, as a man of African descent, those of European decent, we have to deal with the truth of our history. We cannot push it aside, I’m surprised, when I read [Douglas A.] Blackmon’s book — Blackmon is from Alabama — “Slavery by Another Name,” I knew that story. I knew the songs, Sam Cook sang the song: “Working on the Chain Gang.” I knew that story. We know where blues come from, and everything as well. We knew those stories. But Blackmon said, “Wait a minute, the narrative that I have been a part of my life growing up in Alabama, there is something wrong with this narrative. Let me do some investigation, let me do some truth seeking.”

And that’s what he did. He did the truth seeking. He said, “Wait, this pattern of criminalizing black men. That’s real!” “Joe Turner’s Come and Cone.” August Wilson’s play. The center of that play is about Herald Loomis, who comes up to Pittsburgh looking for his daughter after he had taken off the street, had not been in contact with his wife and daughter, and cast in some sort of world for seven years in which he was a slave in some sense. So all those kind of things are true parts of history. So what it is? Brian Stevenson is opening in April in Montgomery a lynching museum to talk about the issues of lynchings and violence. And all these are real parts of our history [that we cannot ignore]. The process in different forms continues, and I think that’s all we’ve said and that’s what women are saying right now. So, hopefully, despite that we have had a women’s movement, a women’s liberation movement, and everything else, hopefully, we will understand on so many levels the abuse of power, abuse of gender power in all aspects and those who are most affected and those who are also still victimized by it (applause).

Joseph Scrivner: I didn’t know, until I was preparing for this, that you led or participated in a protest at San Francisco State in the sixties as a student, and you were part of a five-month strike until they agreed to have a Black Studies Department. Was that your first real engagement with activism? Was there a moment when you decided you were going to jump in and be a part of it? What do you recall about that, and how has it been a part of your activism since then?

Danny Glover: It’s very interesting. I was talking about San Francisco, such a relatively small black population, and they define communities they lived in. I remember there is a place in a community in San Francisco referred to as Harlem West, and that’s in the Fillmore District; it’s a traditionally black community in San Francisco, right adjacent to Japantown, the Japanese community at the same time. So you have these two communities connected to each other. In the forties and fifties, Louis Armstrong was there and Duke Ellington. The Count Basie band played at the Booker T. Washington Hotel because San Francisco had segregated places that black people could stay. So, my first involvement was when I about nineteen or twenty years old. We know about this, we have this period of re-development of these communities, and San Francisco’s housing stock is really pretty old in the sense. A lot of the houses had not been burned down by the 1906 earthquake were Queen Ann’s, Victorian’s Queen Ann’s and Edwardian, built before the turn of the twentieth century and right after the turn of the twentieth century.

So I got involved in that, because what’s so fascinating about the engagement that it was multiracial in that. And I was nineteen or twenty years old. Those were the first meetings I had gone to, going to those meetings and listening to that. What was so amazing was that my dad accompanied me to some of those meetings early on. So we go in and people were trying to say how do we empower ourselves at this moment when we see that we were powerless in what was happening. [So under the leadership of a Japanese American] a lot us went to those meetings at the YMCA and men, women, families, workers came collectively came together in the service of saying “how can we empower ourselves in that moment?” I happened to come out San Francisco State at the moment of extraordinary activism. A number of students had been working in the South, working in Mississippi and Alabama, and everything else. They were migrating back to school and they came to San Francisco. Mario Savio, who started the Free Speech Movement at the University of California at Berkeley, was part of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee down in Mississippi. So they came back and they were activists. So these activists were on campus at the time. They were not only political activists, they were artists as well.

We started a community communication project, which included drama, poetry, dance and music. The idea was how do we engage the community. So that’s the first thing that I was involved in as a student, and the first time I ever stepped up on a stage as well. I had never been on a stage. Anybody told you I was at the church play, they fabricated something. My mom said you couldn’t get me to say two words together at that age. Then in the fall of 1967, we invited Nathan Hare, a professor of history and black studies at Howard University. We invited him out for a year. And we began to develop what we thought should be a Black Studies Program. And all of us, this cadre of men and women that I was around at the time, we read extensively.

By 1970, we were reading poets and artists, talking about all these different kind of artists. We wanted to include all of that. So it wasn’t any African American studies, but also the diaspora studies as well, and the connection between the two. And so we began to develop of that, and we talked to the President [John Henry] Summerskill, who was a liberal, spent time in Africa, president of San Francisco State. We talked with him about how we can manifest these ideas, and it wasn’t approved, so we called the strike in October–November 1968, a student strike. We didn’t realize that Asian-American students, Hispanic-American students, and the Native-American students, had their own grievances, and they all joined the strike, as well as faculty. So basically, it shut the campus down for five months. It wasn’t just African-Americans. So what emerged out of that, in its forty-ninth year, is the School of Ethnic Studies [College of Ethic Studies today] at San Francisco State. It’s still there, and I’m still engaged with it. But it was part of a process that wasn’t just us. I want to make that very clear because sometimes my fellow classmates would talk about “we did this.” I would say “wait, wait, wait, what made this possible was not simply the fact that it was by people of color, and progressive whites as well. What made it possible was that and the fact that we brought the communities in. We had made those strong connections in our communities, whether it was the Latino community, African-American community. So we made those connections. So we had enormous community support behind that. That’s what made it so successful (applause).

Joseph Scrivner: I see this connection for you that you are a truth seeker and a truth teller, both as an actor and as an activist. And you co-founded Louverture Films in 2005. How does that grow out of this past that you shared with us, the work you have done. It sounds like that’s a part of your desire to tell the truth, to present these human truths. Tell us more about that work of yours.

Danny: I began watching African films in the mid-seventies. A friend of mine had a film festival in San Francisco, Clyde Taylor, retired NYU professor, the Clyde Taylor Film Festival. So we see all these African-American films. I was just amazed by the content of them most happens post decolonization, new independence, and new images in which they saw themselves. So, I began to meet at … especially when I met Mandela in 1986 … I’ve done about seven films on the content of Africa, “Bopha,” “Mandela,” “Boesman and Lena,” which I did with Angela Bassett, “Bàttu,” and “The Children’s Republic,” a movie I did in Mozambique. I did several films and produced some films on Africa. I was on the set of a film when a friend of mine, who is the minister of culture [of Mali] and a wonderful filmmaker Cheick Oumar Sissoko, and he asked me to do a cameo in his film. And I didn’t know that I was going to meet this woman who is just extraordinary, Joslyn Barnes, writer and producer. And if you know about the writing in the twenties, Djuna Barnes, who was her great aunt, had the galleys of James Joyce’s “Ulysses,” which is one of the great pieces of literature ever written. She gave it to her great niece and Joslyn said, “I don’t think any human being should own this,” so she donated this in the name of her great aunt to the University of Maryland, where her papers are. We started talking about the Haitian Revolution. I read a book called the “Black Jacobins,” by C.L.R. James, a Marxist historian and one of the great historians of the 20th century. He looks at the Haitian Revolution in relationship to the French Revolution. There are three revolutions that happened in 15 years — 1776, the American revolution; 1789, the French Revolution; and in 1791, the Haitian Revolution, but nobody’s talking about the Haitian Revolution.

And there’s a little bit of history too, because I fancy myself as a historian to some extent. So the Haitians defeat Napoleon’s army in Haiti, led by his brother-in-law [Charles Victoire Emmanuel] Leclerc, in 1803, and by January 1st 1804, they formed their own nation. Napoleon, so desperate for money, sells a piece of land for $13 million dollar, something called the Louisiana Purchase. You never knew why he was doing that, because he was so desperate for money. People never knew about that. It was a gift to this country, because Jefferson was simply interested and fascinated with New Orleans. So they sold the whole thing to them. And because of the revolt of these Haitian slaves, which defeated the largest Armada, the largest group of assembled armies in history till that time and defeated them soundly. I was fascinated by that story and everything else. So when I met Joslyn Barnes, the first day we are on the set in Dakar, Senegal, late at night, all night, shooting a night scene, and that’s all we talked about. That was in 1999 and we haven’t stopped talking since.

We have a film that’s now on the short list for Oscars this year, it’s called “Strong Island.” It’s on Netflix and it’s quite extraordinary. Just last night, at the awards ceremony in New York, it won all the major awards in documentary film awards. It’s by Yance Ford. And we’ve had success with “Soundtrack for a Revolution.” Someone I was just talking to said that their niece worked on the “Soundtrack for a Revolution.” [It’s about] the music of the civil rights movement sung by contemporary artists John Legend, Mary Mary, Richie Havens, and The Blind Boys of Alabama.

We produced a movie that was mentioned about the war on drugs called “The House I Live in” by director Eugene Jarecki, who directed a documentary film called “Why We Fight.” The first time out was a movie called “Bamako,” which is about the Africa debt crisis, a narrative from a brilliant young director from Mali. We produced the film called “Trouble the Water,” which got a nomination for an Oscar about ten years ago and it’s about New Orleans and behind the scenes of what happened with Hurricane Katrina. So those are the kind of works that we produce.

“Toussaint” and the Haitian Revolution is still the film that we want to see done, but in the meantime, we’ve done foreign films as well. We did a film called “White Sun,” which is done by a young director from Nepal. We produced an Argentinian film called “Zama,” which came out this year and looks at pre-colonial period at the end of the 18th century in Argentina. And it has been a platform for a great deal of discussion in Argentina about that period because it’s been done by a really talented filmmaker Lucrecia Martel. And now we want to produce a film about an Adivasi artist. We are looking to do (a film on) Jangarh Singh [Jangarh Singh Shyam, a contemporary artist]. That’s the kind of work that we do.

Joseph Scrivner: Thank you. It looks like you focus on stories that are not told often and people don’t really know.

Danny Glover: Stories essentially — we’ve done primarily documentaries but we’ve also done narratives as well. Quincy Jones was a big, big force in getting “The Color Purple” done. Oprah was a big force in getting the “Beloved” done. And since you are always trying to figure out what do you want to do, what work do you want to do, and I’ve been fortunate to have Joslyn Barnes to learn and grow from.

Joseph Scrivner: I’ve been given the signal that we are about out of time, but I’d like to have one last question for you. I think people have a tendency, with cable television and the Internet, to just sit and become resigned. To shake their heads, what does it mean, what can we do? Given your years of experience in activism, if you could encourage us, briefly, encourage us and tell us to find the thing that we can do to counter whatever negative forces are around us, what would you say to us?

Danny Glover: I have had the pleasure to spend about 15 years around someone who died just a few years ago, at 100 years old, in Detroit. Her name is Grace Lee Boggs. She was married to an African-American, she’s Chinese-American, married to an African-American named [James] “Jimmy” Boggs. Jimmy Boggs was from Alabama. He went to Detroit, became active as a union organizer and a progressive. Always thinking about the world and changing the world. So, you have this union of this African-American man and this Chinese-American woman, and they were dynamite. They spent a lot of time around Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, and they would go on to do things together.

And they talked about revolution evolution — the process of this is, what time is it on the world’s clock right now? Well, we see this happening not simply in the United States, but around the world. We look at issues of climate change, there are things that we can do and we can fight those things. And [also] global warming — even though we see the manifestations of those in places like Florida, Texas and all over, or a minus 100 wind-chill factor in New Hampshire just last week — we understand that and we have to find something [to do about it].

And they talk also about sustainable activism. If I’m thinking about Dr. King and his own evolution, because the Dr. King we saw on August 28th, 1963, is not the same Dr. King we saw right here working on behalf of sanitation workers, April 4th, 1968. It’s not the same Dr. King. When he received the Nobel Peace Prize, he talked about this being a world house, he uses that platform. When he talks about war, he connects war, race, and materialism — prophetic. This was in 1968, 50 years ago he talked about that.

How do we see ourselves. How can we, in ourselves, in our communities, create transformative relationships — the communities of love, a beloved community, God beloved. How do we create that? How do we work toward that? When you work toward something, you begin to have a vision of what the possibilities are. How do we do that? Those are the kind of things that I think about in terms of telling our communities, whether it’s on a campus or whether it’s in a community.

You know, I live in the city of San Francisco, California. Well, I don’t recognize the city anymore. I’ve lived in the same neighborhood since I was 11years old, 60 years. I’ve made trips here and in New York doing the theater and everything but [only] briefly. But I don’t know what that community looks like, I don’t know what that community is. People have moved out through gentrification, and through the “market” — when does a “market” become a disservice to who we are as human beings? (applause) When does a market become a disservice to who we are?

And the first question in philosophy is what — what does it mean to be a human being? Second question is how do you know. And how you know is by what we do in the service of being a human being. So, I think about that. And listen, we have to do what we know, we have to understand. Baldwin said — and I’m paraphrasing — “if we don’t understand our past, we are trapped, and trapped in it.” And if we don’t realize it — we don’t face the truth — not understand and face the truth through our past, we are trapped in it. And what is that past, what is the truth of our past that leads us to our future?

Joseph Scrivner: Ladies and gentlemen, Mr. Danny Glover (applause).